Around two decades ago, Lawrence Summers, then World Bank chief economist, outraged many when he argued in an internal memo that the economic logic behind dumping toxic waste in low-wage countries was “impeccable”. His rationale: less developed countries are “under-polluted” and that “foregone earnings from increased morbidity and mortality” would be lesser in countries with lower wages. Cut to now and the thing to ask is: does India too believe that importing the world’s trash makes for good economics?

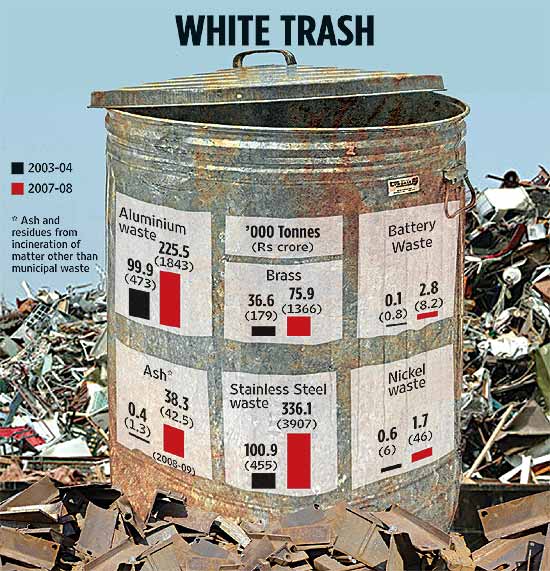

Trade figures illustrate how imports of hazardous waste into India have been growing precipitously in the last few years. It’s now serious business, worth thousands of crores. And the government seems to be encouraging it, with no care to the great harm it’s putting the local environment and the health of Indians to. To get an idea of the scale of operations, consider this: import of stainless steel waste and scrap went up from 10,08,99,729 kg in 2003-04 worth Rs 454 crore to 33,61,14,900 kg in 2007-08 worth Rs 3,907 crore. The details (see table) were revealed in a recent RTI reply to Ashish Kothari of Kalpavriksh, an environment protection group.

Kothari says, “It shows the dual standards of the West which does not want their backyards polluted but is fine with the developing world being defiled.” It is this liberalised waste import regime that brings in hundreds of thousands of tonnes of scrap, very often hazardous, to be recycled here. And this is the reason for the radioactive accident in Mayapuri in New Delhi, an important recycling market, which caused 11 people to fall seriously ill. The Cobalt-60, authorities now say, most likely was in a consignment of imported metal scrap that came in unchecked at India’s borders.

What is even more shocking is the overt import of downright hazardous stuff. Data from the commerce ministry says India imported 10,111 kg of clinical waste in 2004-05, 27,59,200 kg of battery waste, 500 kg of cobalt waste and scrap, waste pharmaceuticals worth Rs 3.4 crore in 2007-08 and titanium scrap worth Rs 13.81 lakh in 2003-04, among many other harmful substances. “Why import these hazardous substances? Does anybody know the end-use of these products? Is it being dumped?” asks Satish Sinha of Delhi-based environmental issues NGO Toxics Link. Unfortunately, there are no answers.

But why would the government want to import so many tonnes of trash? Well, for one, it provides for a very cheap source of raw material. Often, iron and steel scrap is recycled to produce secondary steel. Then metals like lead, nickel and zinc are retrieved from their respective scraps. Electronic waste, a booming category of illegal waste imports, is used to retrieve copper and, occasionally, gold. Most of this recycling happens in the unorganised sector, which in India functions with few safeguards.

|

Last September, the MOEF also allowed the first legal import of e-waste—8,000 tonnes of it—by Attero Recycling, a firm near Roorkee. The decision baffled many because studies show nearly 60 per cent of India’s four lakh tonnes of domestic e-waste goes untreated and is simply dumped. So why not treat indigenous waste instead of importing foreign trash? Attero COO Rohan Gupta counters that procuring domestic e-waste is very difficult and that his 36,000 tonne-capacity plant treats just about 300 tonnes annually. Toxics Watch Alliance’s Gopal Krishna says that import of hazardous waste will also be facilitated under the ftas currently being negotiated with Japan and the EU. “Often it’s masked as recyclable, reusable material. If the agreements are in national interest, why not make the details public?” he asks.

What’s worrying is that the Mayapuri case is not the first known one involving harmful radioactivity. In ’08, France sent back elevator switches made in Pune because they contained traces of Cobalt-60. The radioactive steel scrap was traced back to Vipras Castings Ltd near Pune, which had imported it from various sources. And ever since radioactive screening began at US ports in ’03, 67 containers of contaminated steel products from India have been sent back. What these instances imply is that several Indian workers who handled the radioactive scrap were also exposed but went undetected and untreated.

Containers with hazardous waste imports are also seized at Indian ports with frightening regularity. In ’07, municipal waste from New York ended up in Kochi and in ’09 Tuticorin port officials detained nine containers of hazardous waste from Spain, Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, including used condoms. This, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. India is on its way to being the world’s trash dump. Nowhere is this feeling stronger than in the ship-breaking industry base in Alang, Gujarat. In the infamous ’06 case of the asbestos-laced SS Blue Lady, the authorities and the SC allowed for it to be dismantled despite vociferous protests.

Those tracking the waste business insist the government must train manpower and boost port infrastructure, like installing radioactive scanners, to keep out hazardous waste. “Presently, customs officials are not in a position to monitor. Very few of them can identify, for instance, toxic waste from tubelights,” says Nityanand Jayaraman, a Chennai-based environmental researcher. Now many are also demanding that the government phase out import of foreign waste gradually while simultaneously increasing recovery of domestic waste materials. “The thinking that waste imports from abroad makes for profits is perverse. Instead, what we must realise is that the loss to the environment and to people’s health is irreplaceable,” he concludes.

APR 24, 2010 08:55 PM 2 | But you need to have better understanding of the recycling industry to write an article on the topic Some scrap imports are acually beneficial. Metals can be recycled indefinetly. Manufacturing aluminum is a very energy intensive process. Aluminum scrap can be recycled for a tiny fraction of the energy used to make it originally. Its an environmmentally sound practice. Perhaps NGOs could train people in how to handle scrap. Obviously we have no need for medical waste and used condoms. Thats just dumping. |

APR 24, 2010 04:40 PM 1 | In addition we also import trash like sanitary napkins, diapers. And this when we cannot provide basic sanitation for our own people. |